Southwest Airlines' Model for Competitive Advantage: Strategy Principles for Business Leaders

- May 24, 2025

Introduction

For years, Southwest Airlines was my go-to example of what a winning corporate strategy looks like. Its unique set of strategic choices, like point-to-point flight routes and an open seating policy, worked together to support its mission of low-cost reliable travel. More importantly, each choice also reinforced and increased the positive impact of other choices. Its strategy created what is referred to as “competitive advantage”. That’s when a company consistently makes more revenue and operates at a lower cost than competitors in a way that can’t be duplicated. Even if a company’s competitor copies one or two smart choices the company has made, the competitor doesn’t get the same positive impact because they’re missing the other parts of the strategy.

By financial metrics, Southwest has consistently outperformed competitors, earning profits every year for almost 50 years. During that time, other major US airlines faced losses and even bankruptcy. But the changes Southwest announced in 2024 and 2025, including adopting reserved seating and bag fees, weaken the impact of its other choices and the support for its low-cost mission. Southwest might become a cautionary tale. But, whether you’re running a startup or an established business, understanding why its strategy worked for decades shows how you can build and maintain a resilient competitive position and avoid making choices that undermine it.

Key Strategy Lessons from Southwest Airlines

What Made Southwest Successful:

- Interconnected choices - Open seating + point-to-point routes + secondary airports

- Strategic reinforcement - Each choice amplified the benefits of others

- Mission alignment - Every decision supported low-cost, reliable travel

What Went Wrong:

- Abandoned core strategic choices (open seating, free bags)

- Broke reinforcing relationships between operational choices

- Shifted from unique positioning to commodity competition

For Your Business: Use choice mapping to identify which decisions create competitive advantage

Industry Context

Air travel is an industry that is prone to commoditization. Most travelers aren’t shopping for an airline. They’re shopping for a way to get where they’re going. There are many options to do that and customers are mostly looking at price. This creates immense pressure to compete on price and reduce costs to remain profitable. That’s usually a recipe for a product or service to become a commodity. Of course, there’s some pressure toward commoditization in any industry. But the pressure on airlines is higher than average.

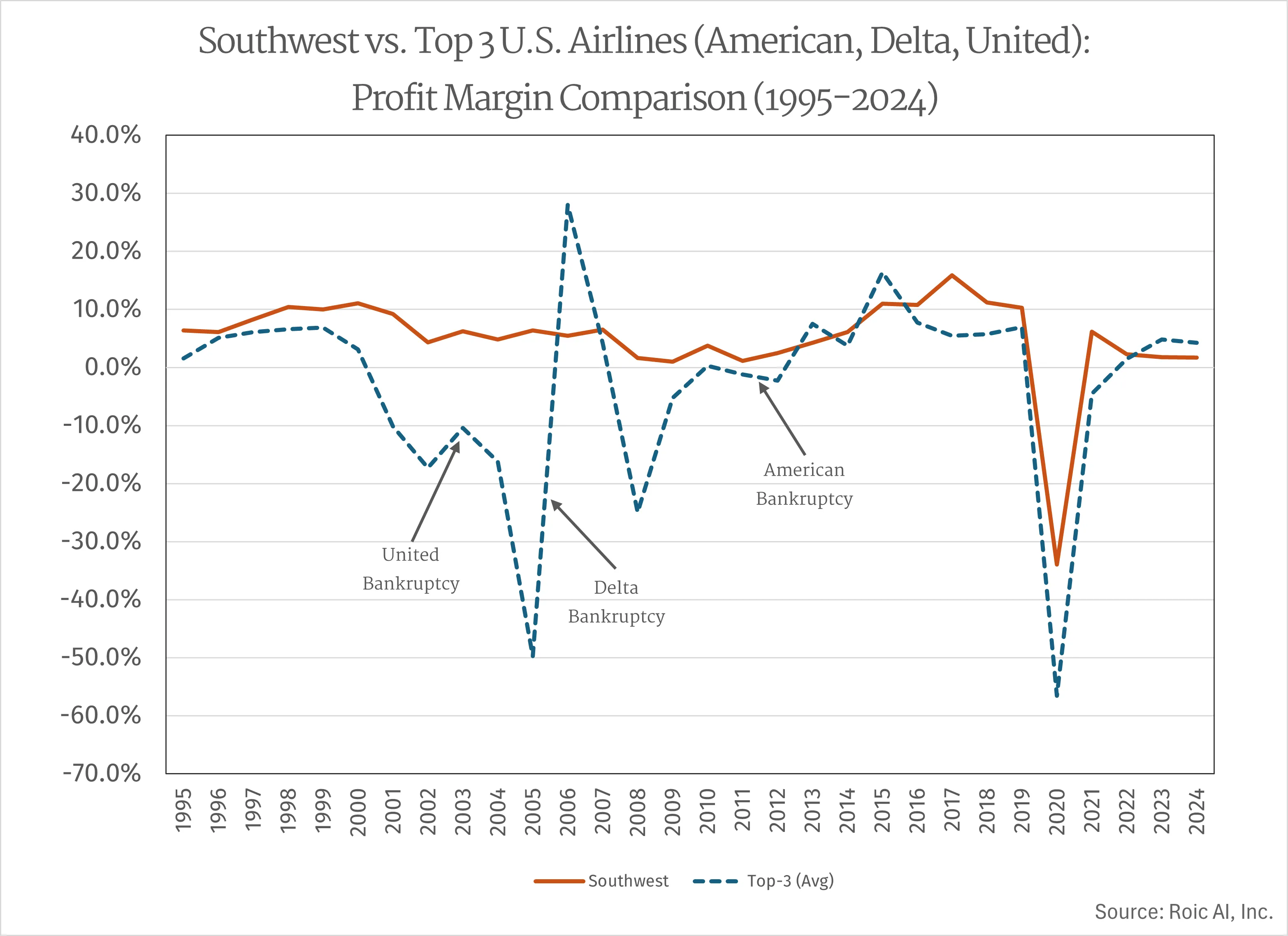

The airline industry also has other unique challenges. It’s notoriously difficult to run a profitable airline due to the high fixed cost of planes, limited and expensive airport gate real estate, complex operations, large staffing requirements, strict regulation, and high sensitivity to economic cycles. Many major air carriers have struggled financially. But Southwest’s strategy has been working very well, by financial metrics.

Until the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Southwest had consistently posted annual profits for decades. It is also one of very few major US airlines to have never filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. The “big three” conventional air carriers, American, United, and Delta, have all filed at least once and have acquired or merged with other large airlines that also filed one or more times.

From its very early days, Southwest took the opposite approach to the incumbent “conventional” airlines in a few key areas. Those choices made its strategy very unique, which is one way to avoid commoditization. Southwest’s ability to maintain profitability while offering lower prices shows that effective strategy can counter even very strong industry pressures.

Southwest’s “Purpose” and “Vision”

But, before thinking about strategy, a company needs to start by understanding what it is actually trying to do. Why does it exist? What’s important about its mission? Southwest’s goals are specific enough to design a strategy around and clear enough to simplify decision-making. Those are a couple of the hallmarks of a useful mission. As of the time of writing, Southwest has published a “Purpose” that reads, “Connect People to what’s important in their lives through friendly, reliable, and low-cost air travel” and a “Vision” stating it wants to be, “the world’s most loved, most efficient, and most profitable airline.” Within these statements, there are four core goals that relate to the major changes Southwest recently announced.

Offering “low-cost air travel” simply means Southwest wants to be known for having consistently lower prices than its competition. That’s only sustainable if it costs it less to operate each flight than it costs its competitors. This relates to its second goal of “efficiency”. For an airline, efficiency means getting as much flight time as possible from expensive, fixed-price people and resources (airport fees, planes, crew and personnel). In other words, Southwest needs its planes in the air as much as possible. The third goal of interest, “reliability”, is a major way an airline can use its resources as efficiently as possible. If flights are constantly delayed, then customers miss connections, crew and personnel “time out” due to too many hours on duty, and Southwest can’t operate as many flights. Southwest will achieve the fourth core goal of “profitability” if it maximizes efficiency and reliability. The more flights Southwest runs using its fixed people and resources, the more profitable each flight will be. A well designed strategy will support all four of the core goals.

To build the right strategy your business first needs to clearly state its goals. Then, understanding the dynamics of your industry, you can make choices that support those goals. Goals should reflect an intentional and unique positioning within an industry. Maybe you don’t want to be a low-cost provider at all. For example, you can read the website of Taipei-based STARLUX airlines top to bottom and, even in the description of their lowest cabin class, you won’t find references to “low cost” or “affordable” anywhere. You will instead find words like “high-end”, “tranquility”, and “comfort”. Pursuing those ideals requires very different strategic choices from those required by a low-cost provider. Before thinking about strategy, make sure that your company knows what its mission is.

Elements of Southwest’s Strategy

Before looking at Southwest’s strategy in detail, it’s a good idea to understand what a strategy is. I think of strategy as the sum of all the choices a company makes. Every company makes at least a few different choices from its competitors, so every company’s strategy is unique. Since strategy is simply a set of choices, it’s critical that each choice is carefully chosen to support, reinforce, and increase the positive impact of other choices.

For example, in any industry, a low-cost, high-volume provider like Southwest needs to make choices that contribute in some way to efficiency. Even if those choices aren’t directly related to efficiency. Any choice they make that helps or encourages efficiency in some way is what I call a supporting choice. Offering only nonperishable packaged snacks on flights isn’t directly related to efficiency, but ground crews don’t need to load and store fresh prepared meals, which reduces the time to service the plane between flights. Choices can also mutually support each other. In general, Southwest focuses on getting flights from deplaning back to takeoff as quickly as possible. That turnaround efficiency supports reliable flight connection times, which in turn support more reliable turnarounds. These are the most powerful types of strategic choices, which I refer to as reinforcing choices. If competitors try to copy some of the choices in a strategy that has many reinforcing and supporting choices, they can’t get the same benefit because they’re missing the rest of the choices. That’s what creates competitive advantage.

Southwest made several choices that are very different from those made by conventional airlines. Because those choices support Southwest’s goals and reinforce its other choices, they have created lasting competitive advantage in a challenging industry. It’s worth looking at a few of those choices in detail to see how they created a strategy that has, at least so far, worked uniquely well for Southwest.

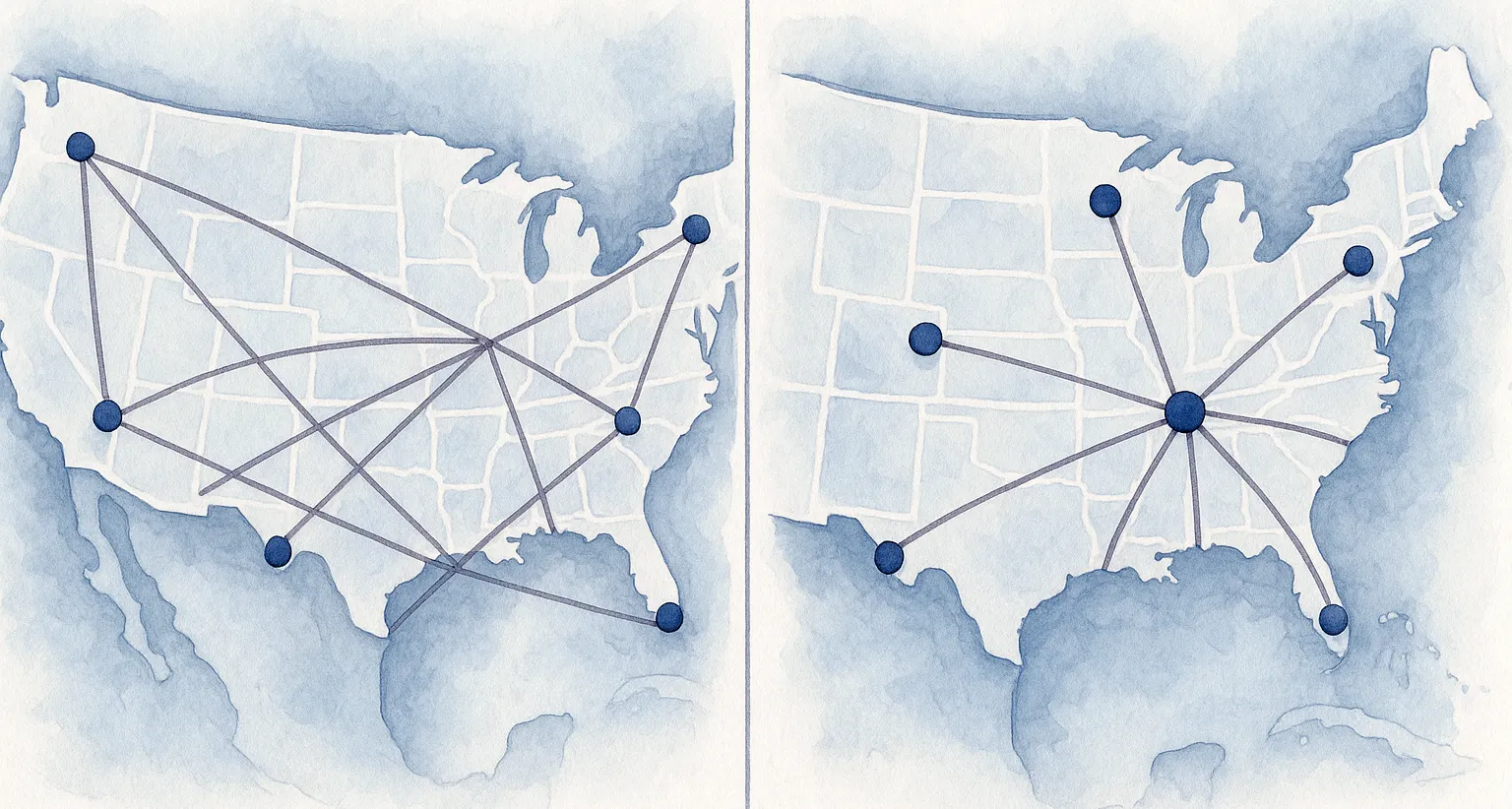

Flight Routing Choices

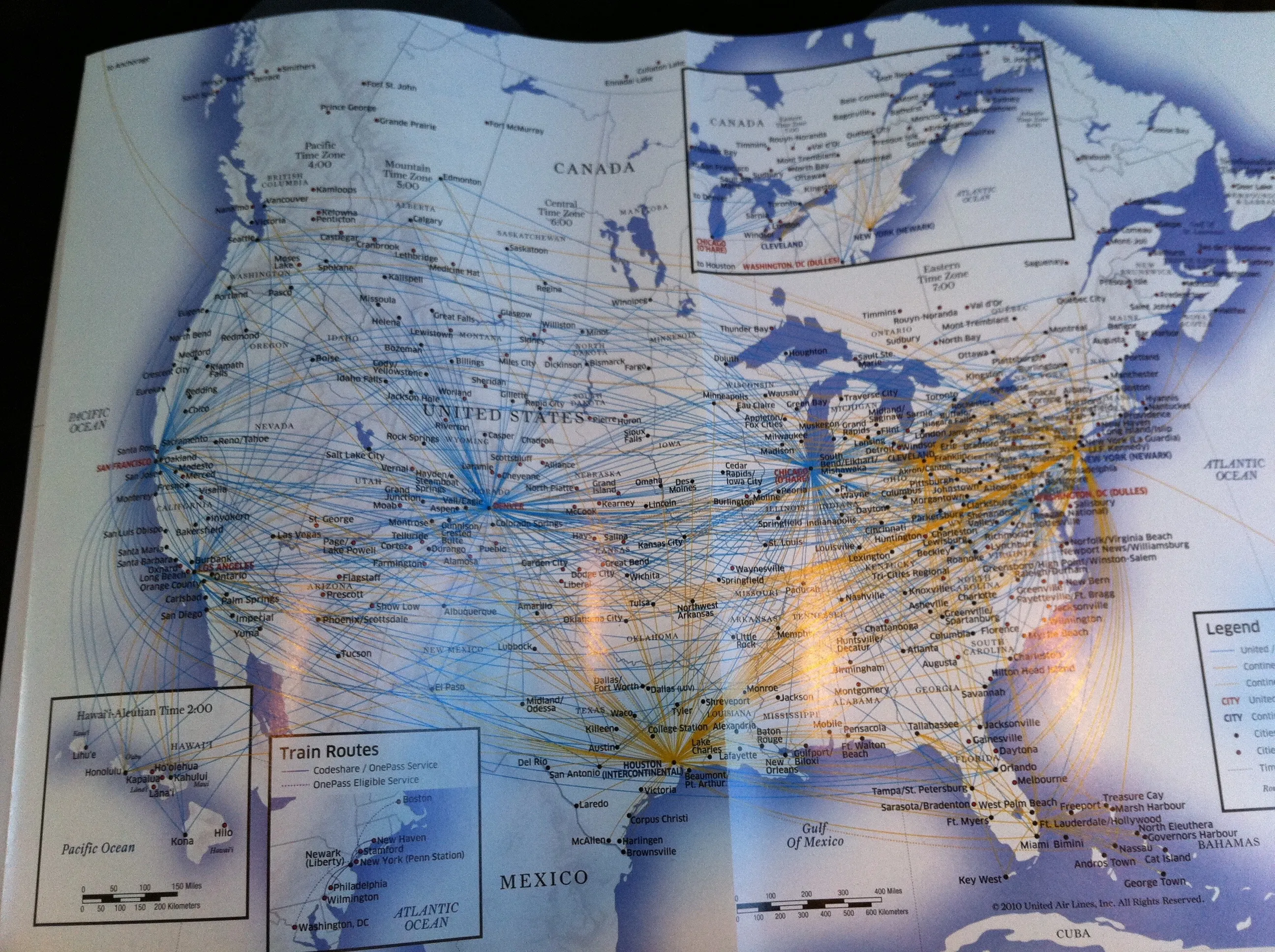

Conventional airlines typically use what’s called a “hub-and-spoke” model for flights. If you’re flying into a small- to mid-sized market on United Airlines, for example, you’ll connect somewhere like San Francisco, Denver, or Chicago, depending on where you’re going. The idea with the hub-and-spoke model is to fly a bunch of flights into and out of a small number of hub airports. The airline gets passengers to the nearest hub, they wait and change planes there, and the airline flies them out from the hub to where they’re actually travelling. On the United Airlines route map from 2010, for example, you can see the hubs cities with route lines radiating out in all directions like the spokes on a bicycle wheel.

Figure 1: United and Continental Airlines Route Map 2010

Figure 1: United and Continental Airlines Route Map 2010

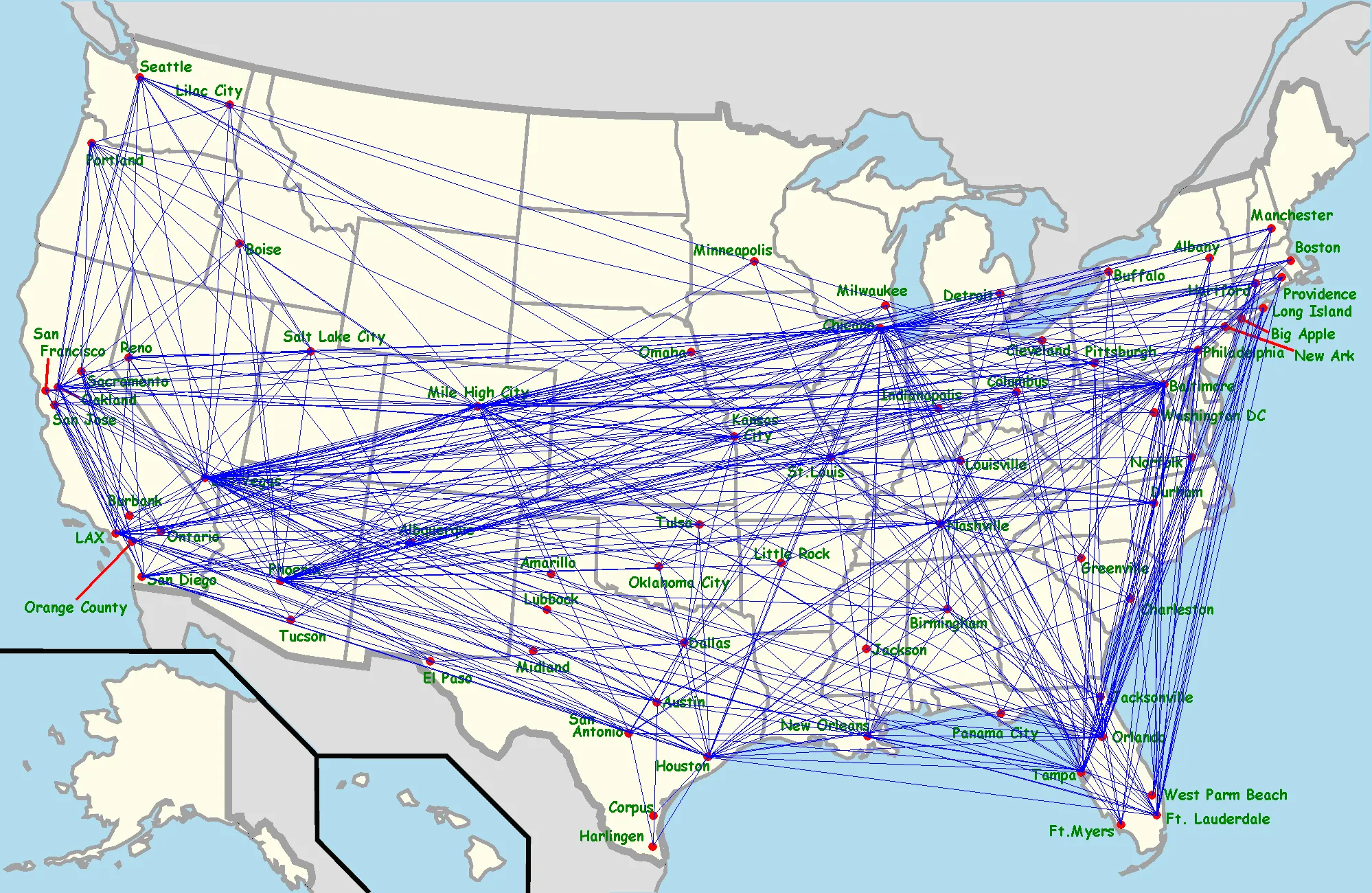

Southwest, in contrast, uses what is called a “point-to-point” route model. To support longer-distance trips, instead of routing flights to the same hub airports, Southwest usually strings together flights through multiple cities in the direction of travel. So, if you’re going from California to Kansas, your best option on Southwest might be to fly a route like Los Angeles to Las Vegas to Wichita. If you’re travelling farther across the country, there might be multiple stops, like Los Angeles to Phoenix to Denver to Baltimore. In the point-to-point model, the route map looks like a series of longer routes with stops in cities along the way. On the Southwest Airlines route map from 2011, there are clearly some cities that Southwest uses more than others, but you don’t see obvious hubs with flight routes in every direction like you do on United’s map.

Figure 2: Southwest Airlines Route Map 2011

Figure 2: Southwest Airlines Route Map 2011

By not using hubs, Southwest supports lower costs because it has more flexibility to choose “secondary” airports that aren’t as heavily used by conventional carriers. These airports have less competition for gates, so they charge lower fees. The hub-and-spoke model is less complex because the airline can consolidate its operations in a few airports. But it creates a high interdependency between an airline’s flights. It also concentrates the risk of congestion and delays in a few airports. Let’s say Denver has a big snowstorm. Since United routes hundreds of flights through that airport, hundreds of flights will be delayed or cancelled. Airline efficiency requires fully utilizing personnel and resources. If hundreds of flights are impacted, that’s a lot of planes, gates, and people that can’t do anything. Southwest does route some flights through traditional hubs like Denver. But by designing its route map in a linear fashion, its use of airports is more evenly distributed throughout the area it covers. This limits the impact of delays, increases efficiency, and directly supports its goals.

Flight Scheduling Choices

The point-to-point model can lead to some unexpected routes. But some people do, for example, need to fly from Las Vegas to Wichita. Southwest is probably the only airline that flies that route nonstop. United can only get you there in a reasonable amount of time if you change planes in Denver. In addition to seeing less common routes, if you look carefully at Southwest’s route map, you’ll notice a lot of shorter flights. Southwest’s flights usually aren’t longer than three or four hours. This isn’t a coincidence. The point-to-point route model makes it easier for Southwest to expand its service area by adding cities that are near to airports it already serves. Conventional airlines need to plan more carefully to add shorter routes because they need a nearby hub to connect to. Avoiding the use of hubs gives Southwest more control over the length of its flights. In strategy terms, Southwest’s choice of route model supports its choice to target shorter routes by making it easier to do. An airline that uses hubs can try to target shorter flights, but its options for routes are more limited.

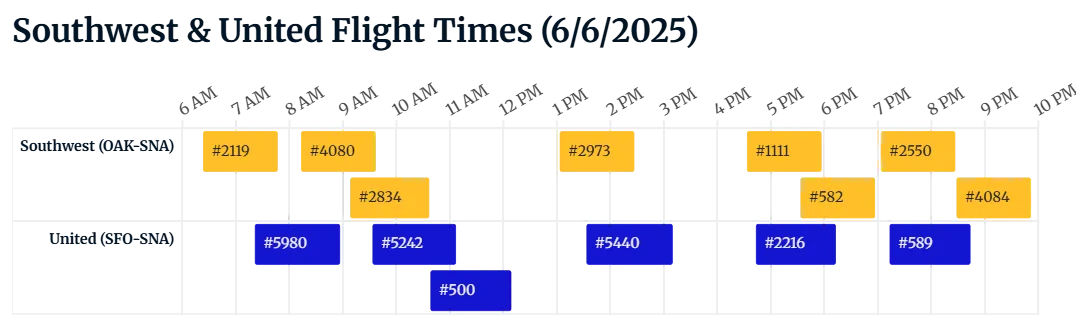

But why would an airline want to fly shorter routes at all? Because many shorter routes actually have a lot of passenger demand. Southwest can identify a pair of cities with consistent demand and have planes in the air on that route practically all day. I used to fly regularly within California from the San Francisco Bay Area to Orange County in Southern California. I would always fly on Southwest because it was cheap and easy to book, even at the last minute. That’s because they ran so many flights along that route. At the time of writing, Southwest operates as many as 16 flights per day back and forth between Oakland, CA and Santa Ana, CA. Each flight is scheduled for about 90 minutes. Having planes in the air all day on a popular route supports Southwest’s full utilization of its expensive resources and people. So, Southwest’s flight scheduling supports its goal of efficiency, but comes with tradeoffs.

By focusing on certain shorter routes, Southwest has accepted the tradeoff that they need to turn flights around quickly. Otherwise they aren’t using their expensive resources and people effectively. With longer routes, it’s easier to fully utilize planes and crew because flights are in the air for a long time. That means less time spent on the ground loading and unloading, servicing planes, and changing crew. There’s less overhead. But, with sixteen 90 minute flights each day between Oakland and Santa Ana, Southwest’s efficiency enables them to pack 24 hours of flight time per day on that route. Conventional airlines will try to compete on some of those shorter, popular routes. But they typically can’t match the volume of flights that Southwest can handle. On the same peak travel day of Friday, United flies only 12 one-way flights per day from San Francisco to Santa Ana, versus Southwest’s 16 flights from Oakland (near San Francisco) to Santa Ana.

But why don’t conventional airlines simply plan for more efficient schedules, copying what Southwest does? One reason is the hub-and-spoke model. They need to get a lot of passengers to and from their hubs because so many itineraries connect at a hub. United needs to accommodate all of the connecting flights. The San Francisco to Santa Ana route is impacted by this. Many customers are travelling from somewhere else and are only connecting in San Francisco, a major United hub, so they can get to Santa Ana. Spacing out the flights helps United to accommodate different connecting flight times from cities around the country. while filling as many seats as possible on each plane. In contrast, Southwest can focus on creating more direct flight paths along popular routes, without needing to route connections through hub cities. But to make flights with connections competitive with longer nonstop routes, it needs to to turn its flights around with no delays. Its other choices give it more control over one important cause of delays: the passengers.

Passenger Experience Choices

On a conventional airline, there’s no real incentive for passengers to get seated on the plane quickly. Everyone is assigned a seat by the time the flight is ready to board. Also, even with assigned seats and boarding groups, people in the aisle and middle seats slow down the boarding process when they stand up to let people get to their seats. Some people manage to end up in the wrong row and have to climb backwards through the crowd. People travelling together are not seated together, so they’re slowing things down further by trying to switch seats or talking with the people they’re travelling with. From its inception, Southwest recognized that its unique flight routing required efficient turnarounds and adopted open seating instead of reserved seats.

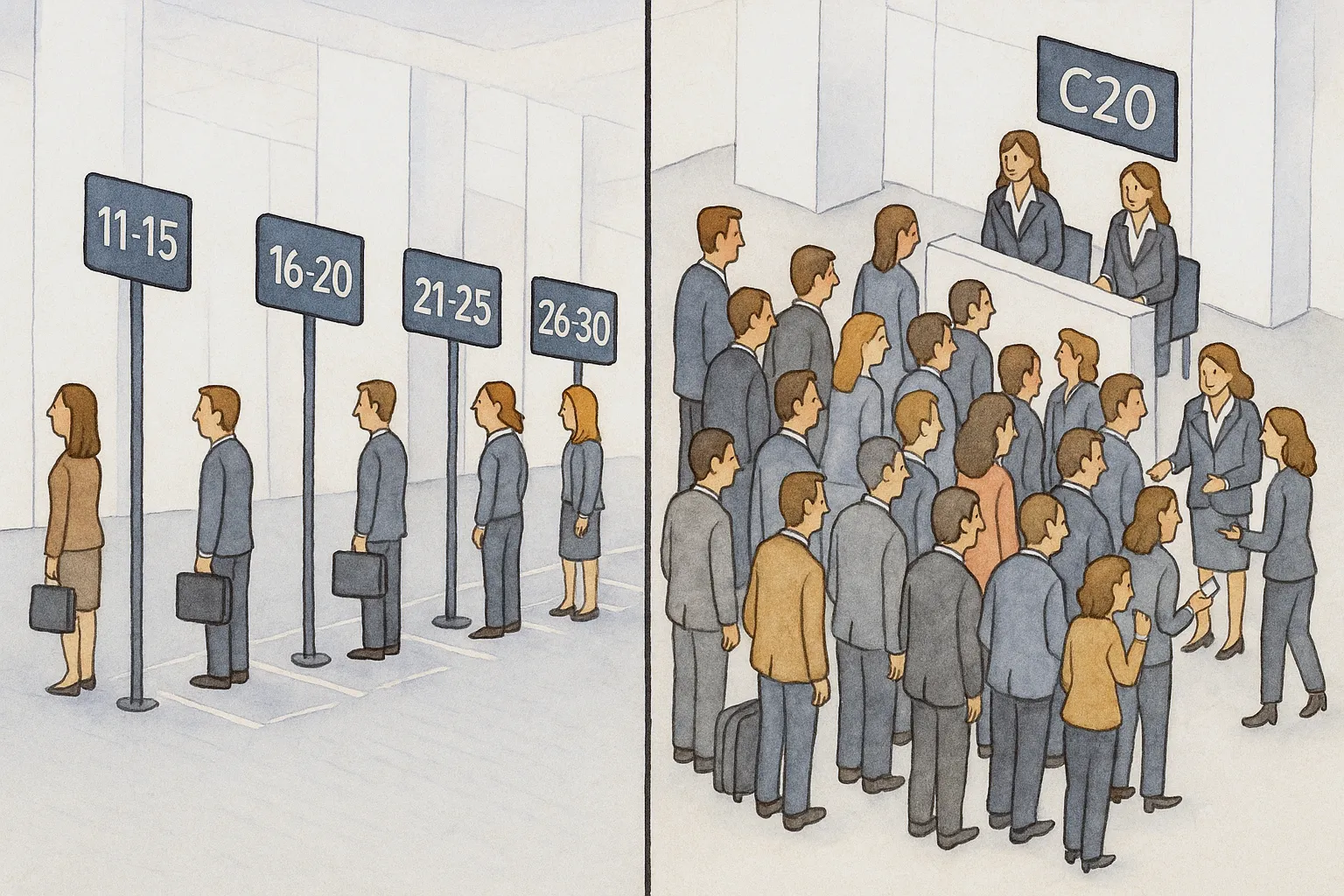

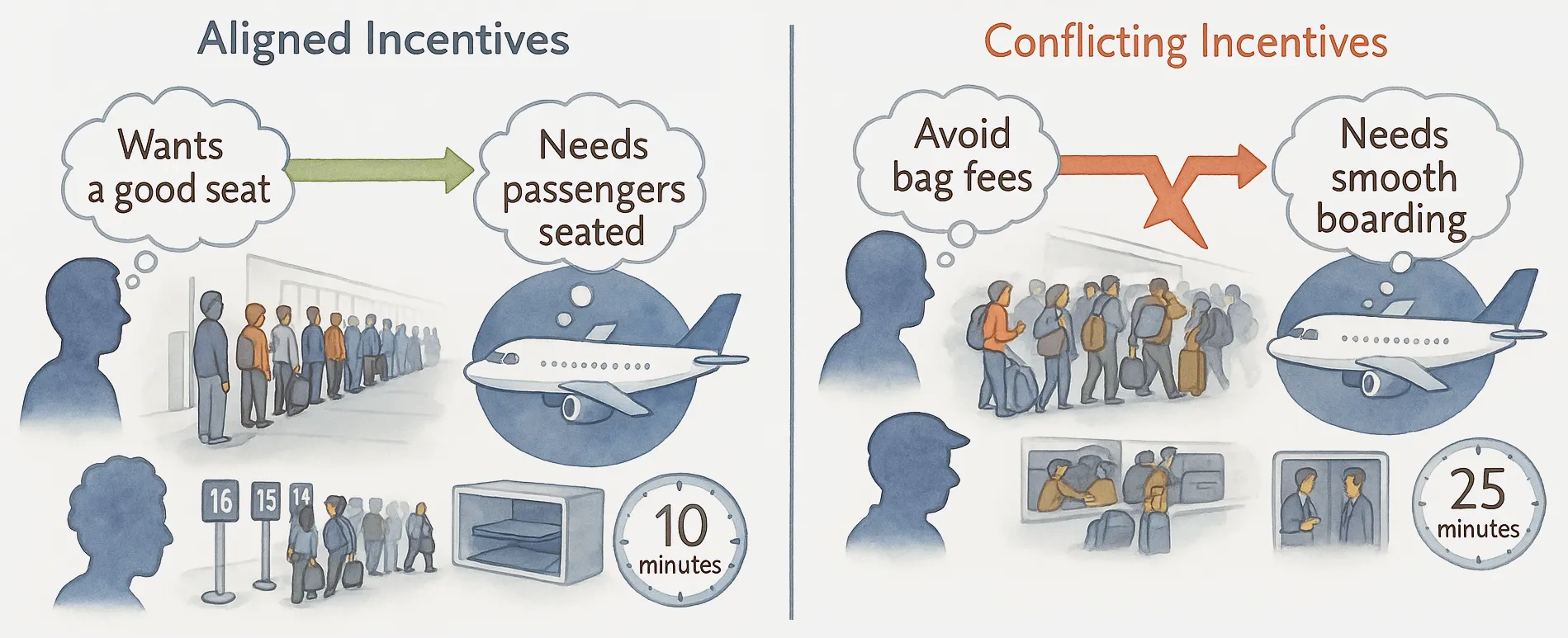

Open seating aligns the passengers’ and the airline’s incentives. To reserve your preferred seat, you have to get on the plane and sit down. That’s also exactly what Southwest needs you to do. A related choice is Southwest’s boarding order. In case you’ve never taken a Southwest flight, I’ll set the scene. When you check in, you’re given a letter and number that tells you your exact place in line. Each gate has a designated “lining up” area with numbers, so everyone can stand in the exact order they’ll be boarding. There’s no need to line up before your group is called, because your exact place in line has already been determined. Everyone on a Southwest flight lines up in an orderly fashion at exactly the right place when their group is called and boards the plane as quickly as they can because they want to grab a good seat.

Everything I’ve just described is the opposite of what happens when boarding a conventional airline. You’ve probably experienced this yourself. People line up at the wrong time, they block the boarding area, and they try to board before their group is called. The Southwest boarding model is faster, and you don’t have to take my word for it. Esteemed experts, the MythBusters, proved that open seating is the most efficient way to board a plane. They created a realistic replica of the air travel experience, complete with a boarding gate area and a plane interior with more than 150 seats, overhead bins, flight attendants, and passengers doing common things that can cause delays, such as boarding with children. They tried several boarding approaches including the method most commonly used by conventional airlines, where rows board from the back of the aircraft forward, as well as Southwest’s open seating. The conventional method took almost 25 minutes, while Southwest’s method was about 10 minutes faster.

It’s worth considering why conventional airlines wouldn’t simply eliminate reserved seating to make their boarding process more efficient. It’s because the other choices they made are incompatible with open seating. We saw earlier how it’s more difficult for conventional airlines to fullly utilize their planes on shorter, popular routes because of their choice of a hub-and-spoke fight routing model. Similarly, they are limited in what they can do to speed up boarding because of other choices they’ve made.

For example, conventional airlines usually have multiple cabin classes, such as premium, business, or first class. These are assigned at the time a passenger purchases a ticket. Open seating across the plane simply wouldn’t work. Even if they made each cabin class “open”, people would, of course, try to sit in seats for classes they hadn’t purchased. It would be a nightmare when the premium sections inevitably ran out of seats for passengers who had paid for those sections. Without assigned seat numbers, flight attendants would have to interrogate each person in the section seat by seat to figure out who snuck into a cabin class they didn’t pay for.

And conventional airlines can’t eliminate those multiple cabin classes because of how their frequent flier programs work. A main reason their customers are loyal is that loyalty gives them status and entitles them to upgrades to better cabin classes. Eliminating the cabin classes would destroy the value of their loyalty programs. Southwest chose to only have one cabin class because that supports its choices to ahve open seating and a predefined boarding order. There are some seats that are preferred on Southwest’s flights, so it gives passengers with status or premium tickets early spots in the boarding order, so they can grab those seats if they want them.

Another unique choice that Southwest Airlines made to give it more control over delays was to not charge for checking baggage. It’s difficult to imagine now, but it was only about 15 years ago that all of the conventional airlines let you check bags for free. In fact, they encouraged you to do it because it makes the boarding process more efficient. Looking again at the boarding process, if a passenger has a larger carry-on bag, they have to find space in the overhead bins to store it. This process has a lot of issues. The bins fill up as more people board the plane, and people slow the boarding process while they find a bin that can fit their bag. This situation is worse when there are reserved seats because people may need to go past their assigned seat to find a bin and then climb through the boarding line to get back to their seat.

Charging passengers to check bags created a financial incentive for passengers to store as much of their stuff as possible in the overhead bins. This created the current situation with conventional airlines, where carry-on bags slow down the boarding process. Even if a passenger thinks there might not be a place to stow their carry-on bag, there’s no reason not to bring it on with them. Those airlines will check the bag for free if there’s no more room in the overhead bins. The airlines charge passengers less money if they bring carry-on bags. It’s a discount in exchange for making the boarding process less efficient. Instead, Southwest chose to continue allowing passengers to check two bags for free. Like open seating, this aligns the passengers’ incentives with the airline’s incentives to make boarding and deplaning as efficient as possible. That efficiency further supports Southwest’s choice of shorter point-to-point routes.

Southwest’s open seating, predefined boarding order, single class cabin, and free checked bags are individual choices that work together to form a strategy that supports the company’s goals. They aren’t just arbitrary decisions meant to “differentiate” themselves. If a company makes choices that are uniquely designed for its own strategy, their products and services will naturally look “different”. The choices that work uniquely well for your own strategy are less likely to be useful choices for a competitor to copy. Strategic choices aren’t always obvious. But you can learn to spot them, so you can build an effective strategy for your own business.

How To Identify Strategic Choices

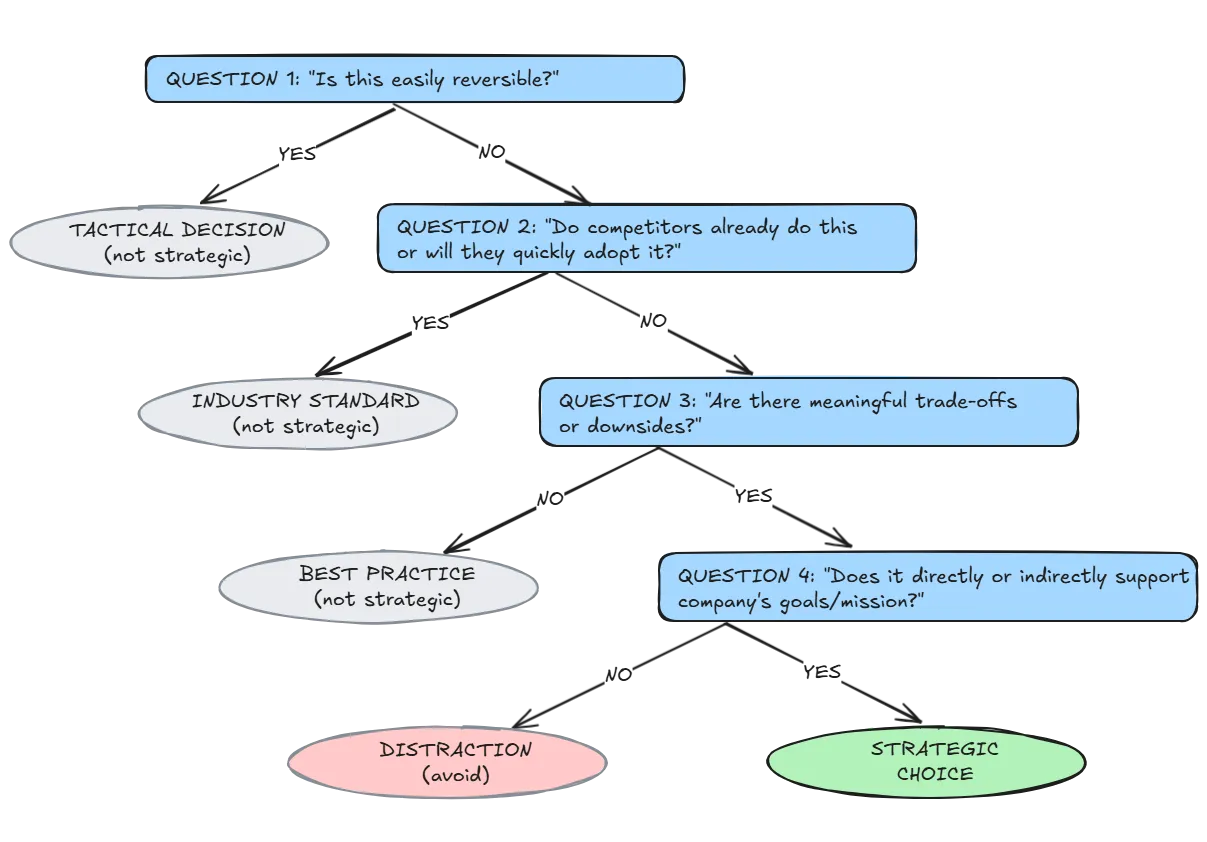

Building a strategy requires identifying the decisions your company has already made, as well as evaluating new ideas. It’s a good idea to make a detailed inventory to understand the choices your company has made so far. You should also write down the things you plan to do, even if you haven’t implemented them yet. A business makes thousands of decisions per day, so you should focus on the ones that will impact your strategy. Only strategic choices are important for this analysis.

Don’t mistake tactical decisions for strategic choices. A tactical decision is usually easily reversible. If there’s an area where you change course often or that is probably a temporary response to industry conditions, it’s probably not a strategic choice. Sometimes it’s easier to spot strategic choices by considering the things you do differently than your competitors. Who you sell to, how you’ve designed your products and services, and how they are delivered to customers are all areas where you’re likely to find important strategic choices.

Another way to identify strategic choices is by recognizing decisions that have trade-offs. A strategic choice almost always has some downsides or risks. If you have a new idea, but there are no meaningful trade-offs, it will eventually become an “industry standard” activity that doesn’t uniquely benefit your company. For example, the first airline with online check-in had a temporary efficiency advantage. Online check-in soon became an industry standard because there were essentially no trade-offs. Every airline adopted it. Online check-in wasn’t a strategic choice because the competitive advantage was temporary.

The most important strategic choices provide durable competitive advantage. By “durable” I mean that it’s impractical or impossible for competitors to make the same choices. Sometimes the rest of a competitor’s strategy prevents it from getting the same benefits from a choice that your company does. Often this is because the rest of your company’s strategy mitigates the negative trade-offs of the choice. That helps to create durable competitive advantage because it’s less likely that your competitor will try to copy the choice. If your competitor does try to copy it, the tradeoffs will prevent your competitor from getting as much positive impact as your company does.

For example, in the U.S. video game industry of the mid-1980s, Nintendo made several choices that created durable competitive advantage. Nintendo chose to drive demand for its home game system, the Nintendo Entertainment System, by ensuring there was a large library of high-quality games available to play on it. Nintendo chose to do this by developing its own games and also by allowing third-party companies to develop games. If Sega, Nintendo’s main U.S. competitor, had chosen to copy the choice to leverage third-party game development, the positive impact would have been limited. This is because Nintendo also chose to require game developers to agree to a period of exclusivity. This meant that the best game developers with the most interesting ideas were captured by Nintendo and couldn’t develop games for Sega, or any other competitor, for at least two years.

By choosing to have other companies develop games for their system, Nintendo had to accept the trade-off of losing direct control over game content and quality. It mitigated this trade-off by additionally making the unique choice to require developers to purchase the physical game cartriges from them. Effectively, the only way a third-party company could release a game for Nintendo’s system was if Nintendo approved of it. Nintendo’s choices gave them a larger and higher-quality game library than any competitor could hope for. For the first two years, the only way for Sega to ensure a quality game library for its own home gaming system was to develop nearly every game on its own. Sega certainly developed some popular games. But, for several years, Nintendo’s competitive advantage made it impossible for competitors to match the demand its game library created for its game system.

Even if a competitor manages to copy a company’s choices, the competitor will be unsuccessful if the choices are incompatible with the rest of its strategy. Conventional airlines have previously failed in attempts to create “low-cost” subsidiaries to compete with airlines like Southwest. “Ted”, one such airline brand created by United, tried to target popular vacation destination cities in the same way that Southwest targets popular routes. But Ted was just United in a friendly costume, so it still had to rely primarily on United’s hubs. This limited its ability to target popular routes and didn’t provide the same cost advantages that Southwest got from the same choice. It also imitated Southwest’s single-class, all economy, seating. But that reduced the value of the frequent flier program it shared with United because there was no premium class of seating to upgrade to. Ted also had assigned seating, which prevented them from gettting the cost and efficiency benefits that Southwest got from its single-class of service. Ted’s choices were incompatible with the rest of United’s strategy, so the brand only lasted about five years.

Evaluating Choices Against Mission and Goals

Southwest’s strategic choices only have positive impact on the business because they support its mission and goals. If a company doesn’t know or agree on what those are, then it doesn’t know why it exists in the world. If you feel like your company is in that situation, you should drop everything and figure it out before doing anything else. There is no strategy if there is no goal. Your mission, vision, or whatever you choose to call it, should clearly and specifically state what you do for customers and how you do it. Each component of a company’s mission should describe a goal.

Furniture company IKEA, a low-cost provider in a different industry, refers to its mission as a “business idea”, which is, “to offer a wide range of well-designed, functional home furnishing products at prices so low that as many people as possible will be able to afford them.” There are three goals in that statement: “well-designed furnishing”, “functional furnishing”, and “prices that as many people as possible can afford”. IKEA makes hundreds of choices in its business with direct or indirect positive impacts on each of those goals.

To build a strategy, your company’s choices need to either directly support your company’s goals or support them indirectly by supporting other choices. When you’re evaluating an existing strategy or considering new opportunities, you should first figure out which of your company’s choices directly support its goals. Sometimes it’s tricky to identify which choices those are. But it’s important to figure it out because they are your company’s most important choices. To do that, it’s useful to think about each goal in a quantitative way.

Your business is trying to increase or do “more” of each goal. A choice that directly supports a goal creates more of that goal. For each choice, ask yourself how easy is it to achieve more of each goal if the choice wasn’t part of your strategy. Does the addition of the choice directly help you to get more of the goal than you would without it? If it does, and you can describe exactly how it does, then that choice directly supports the goal. Another way to think about it is to imagine that it suddenly became illegal for your company to make that choice. Would the goal be directly negatively impacted by that? That’s another indicator that the choice directly supports the goal. To fully understand a company’s strategy, you need to understand not only which choices the company’s goals but also how choices support and reinforce each other.

Strategy as Interdependent Choices

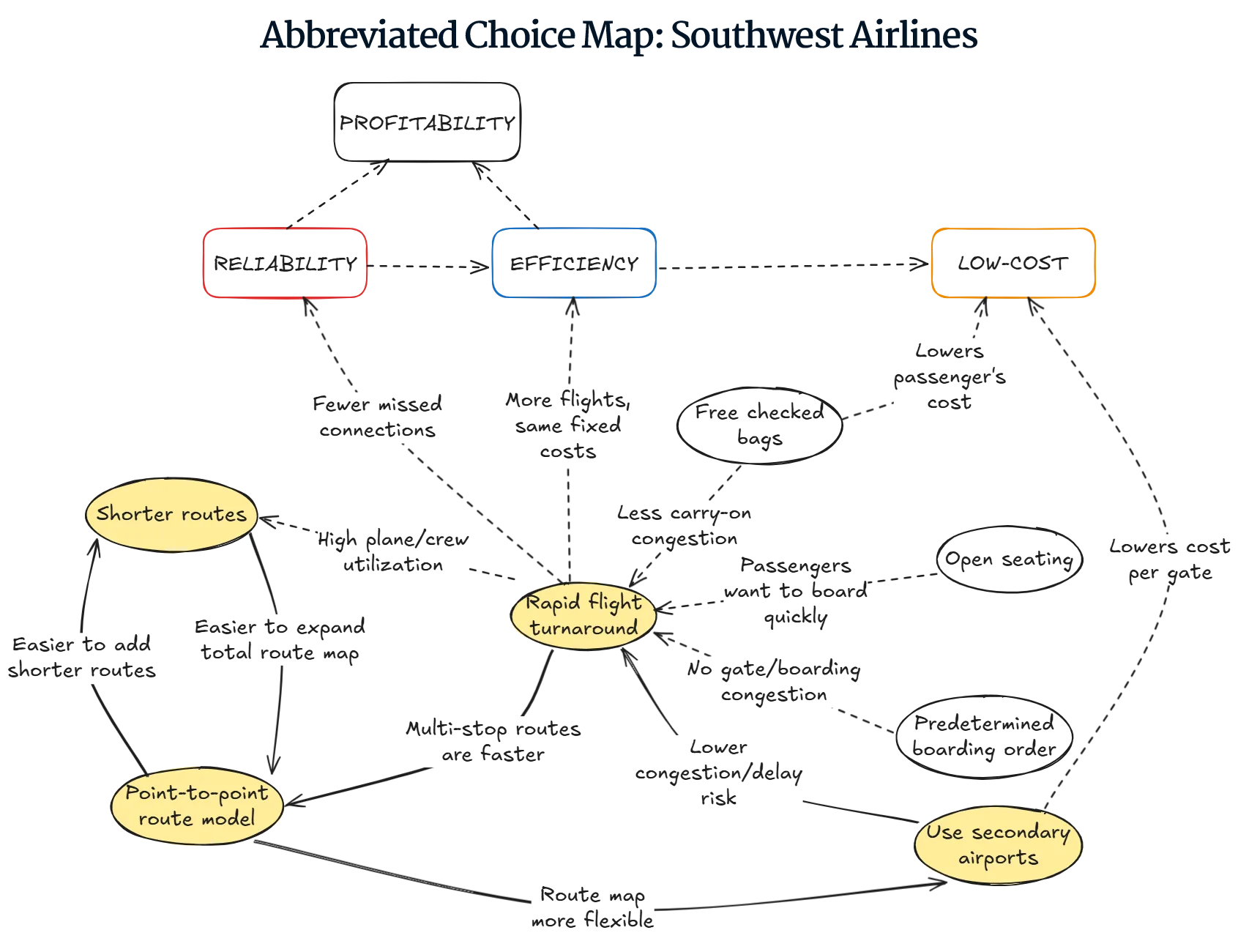

I’ve mentioned the concept of reinforcing choices in strategy. It’s easiest to vizualize how that works using what I refer to as a choice map. Below, you can refer to an abbreviated map of Southwest’s choices I’ve discusssed so far. A complete map would be very involved because there’ve made a lot of strategic choices.

At the top of the choice map are Southwest’s four core goals we looked at earlier. Dotted line arrows indicate which choices directly support those goals. For example, the company’s choice to focus on rapid flight turnaround directly supports the airline’s reliability and efficiency. In other words, without rapid flight turnaround, the company’s reliability and efficiency would both be lower.

There are also dotted line arrows indicating where one choice supports another choice. The idea behind supporting choices is that one choice reinforces and increases the positive impact of another choice. For example, the positive impact of the choice to fly shorter routes is increased by the choice to focus on rapid flight turnaround because that enables them to meet demand on those routes with high utilization of their planes and crew. Free checked bags, open seating, and predetermined boarding order all support the choice of rapid flight turnaround because the its positive impact is increased by the boarding efficiencies that those choices create.

The most interesting and powerful supporting relationships between choices are connected with solid line arrows. Those lines connect choices that have bidirectional support between them. This means that one of the choices supports a second choice, and that second choice in turn supports the first one. I like to refer to those as reinforcing choices and highlight the choices in yellow. They work together to create a larger positive impact to a company’s goals than they would on their own. This means that competitors can’t just copy one or two choices from the company’s strategy and expect to get the same amount of impact. In the subset of Southwest’s strategy in the choice map, there are two sets of reinforcing choices.

Reinforcing Relationship #1: Shorter Routes and Point-to-Point Model

The first is between the “shorter routes” and “point-to-point route model” choices. In one direction, the choice to fly shorter routes increases the positive impact of the choice to use point-to-point flight routing because shorter routes expand the total route map, providing more options to create point-to-point itineraries for customers. Cities on shorter routes can easily become connecting cities from which to continue expanding Southwest’s geography. A conventional airline’s hub-and-spoke routing can’t benefit as much from shorter routes because only flights that connect through a hub will be reliable itineraries for customers.

In the other direction, the choice to use a point-to-point route model increases the positive impact of flying shorter routes because that model makes it easier to add popular shorter routes. With more airports across its flight area that are already used for connecting flights, it’s much easier to target new popular shorter routes by using those airports. For Southwest, the airports on a new route don’t need to include a hub. If a conventional airline doesn’t already have a hub on either end of a popular shorter route, even if it could make a reasonable profit on the route, it is logistically challenging for them to fly it because their operations are concentrated around hub airports. Those airlines can’t take advantage of many of the popular short routes.

Reinforcing Relationship #2: Compounding Advantage in Operations

The second set of reinforcing choices is even more interesting because it is actually a set of three choices: “point-to-point route model”, “rapid flight turnaround”, and “use secondary airports”. Those three choices reinforce one another in one direction, creating compounding advantage.

-

“Rapid flight turnaround” increases the positive impact of the point-to-point route model because the focus on rapid turnaround shortens the total trip time for multi-stop routes, making them more competitive with longer non-stop routes offered by competitors.

-

The “point-to-point route model” in turn increases the positive impact of using secondary airports because that route model makes the choice of airports more flexible, allowing Southwest to choose airports that make the most sense for cost and efficiency.

-

Finally, arriving back at the first choice again, the choice to “use secondary airports” increases the positive impact of rapid flight turnaround because those airports have lower risk of congestion and delays, which makes rapid flight turnaround more effective.

A conventional airline wouldn’t benefit as much from adopting just one or two of these choices because the impact of the supporting choices would be missing. Of course, conventional airlines try to turn their flights around as quickly as possible, but they don’t don’t get as broad a benefit from those efforts because they use a hub-and-spoke route model.

Analyzing Strategic Fit and Reinforcement

A system of mutually reinforcing choices like Southwest Airlines has built creates what strategy experts call “fit”. When there’s fit, a company’s choices complement each other in ways that create more value together than they would as independent choices. To better understand the impact of your company’s choices, it’s useful to create a choice map like the one I created for Southwest Airlines above.

You should start by documenting your company’s goals. You can draw a box for each goal and an oval for each choice. Draw arrows from the choices that directly impact a goal to the box for the goal, to see how your strategy impacts your goals. Not every choice will have direct impact on one or more of your goals, but that’s OK.

Next, if one choice increases the impact of another choice, draw a dotted line arrow to show that support, labeling it with a description of how one choice increases the impact of the other. Be sure to look for support in two directions, which creates a reinforcing relationship. When you find a reinforcing relationship between two or more choices, you can use a solid line to mark those connections so they’re easy to spot.

Choices that don’t connect to any goals or any other choices, or even an “island” of a few choices that don’t connect with the rest, are a warning that there might be a problem with your strategy. It’s possible that some of them are simply tactical or industry standard decisions and aren’t strategic choices at all. Or they may be activities that are costing you time, money, and focus with no real impact on your company’s goals. In the worst case, some choices may be working against other choices, reducing the positive impact on your business.

Sometimes it’s difficult to identify which choices work together in your strategy. I’ve described those relationships as choices that increase the impact of other choices. You can think about each choice one at a time to identify the other choices that work together with it. Every strategic choice positively impacts your business somehow. Think about what the impact of the choice is. Does it help you to get more customers? Does it help you to keep those customers? Maybe it helps you to sell more things to each customer. Or maybe it reduces the cost of providing your product or service to customers. Identify the impact of the choice and consider how big the impact would be if the choice stood alone, without all the other choices. Now, look for other choices on your list that increase the size of its impact in some way. Those other choices have a supporting relationship with the choice you’re looking at.

When you find one choice that reinforces another, reverse your thought process and think about the standalone impact of the other choice. Is it increased because you also made the other choice? If so, there’s also a supporting relationship in the opposite direction. Those choices have a reinforcing relationship. You can document the relationships you find as connections on your choice map, to help visualize your strategy.

When your choice map is complete, you should be able to trace a path from every choice to at least one of your goals. To check this, follow the arrows from each choice to see if there’s a path to get to one or more of the goals. The most important choices have paths to multiple goals. In the example choice map for a subset of Southwest’s strategy, there is a path from every choice to every goal. The paths from some choices to the goals may be longer than others, passing through several choices along the way. Choices with shorter paths to goals have more direct impact on achieving those goals. If you see choices with a long path of support to only one goal, those choices may be diluting your strategic focus. Although they provide indirect support to part of your mission, if they are particularly expensive or conflict in some way with other choices, you might be better off not doing them.

By understanding the choices that will have lasting positive impact on your goals, you can avoid abandoning changes that give your company durable competitive advantage. In a well-designed strategy, the easiest way to lose competitive advantage is to voluntarily abandon reinforcing choices with direct positive impact on your goals. Unfortunately, as of the time of writing this memo, that is exactly what Southwest announced they’re going to do.

Southwest’s Strategic Changes and Predicted Impact

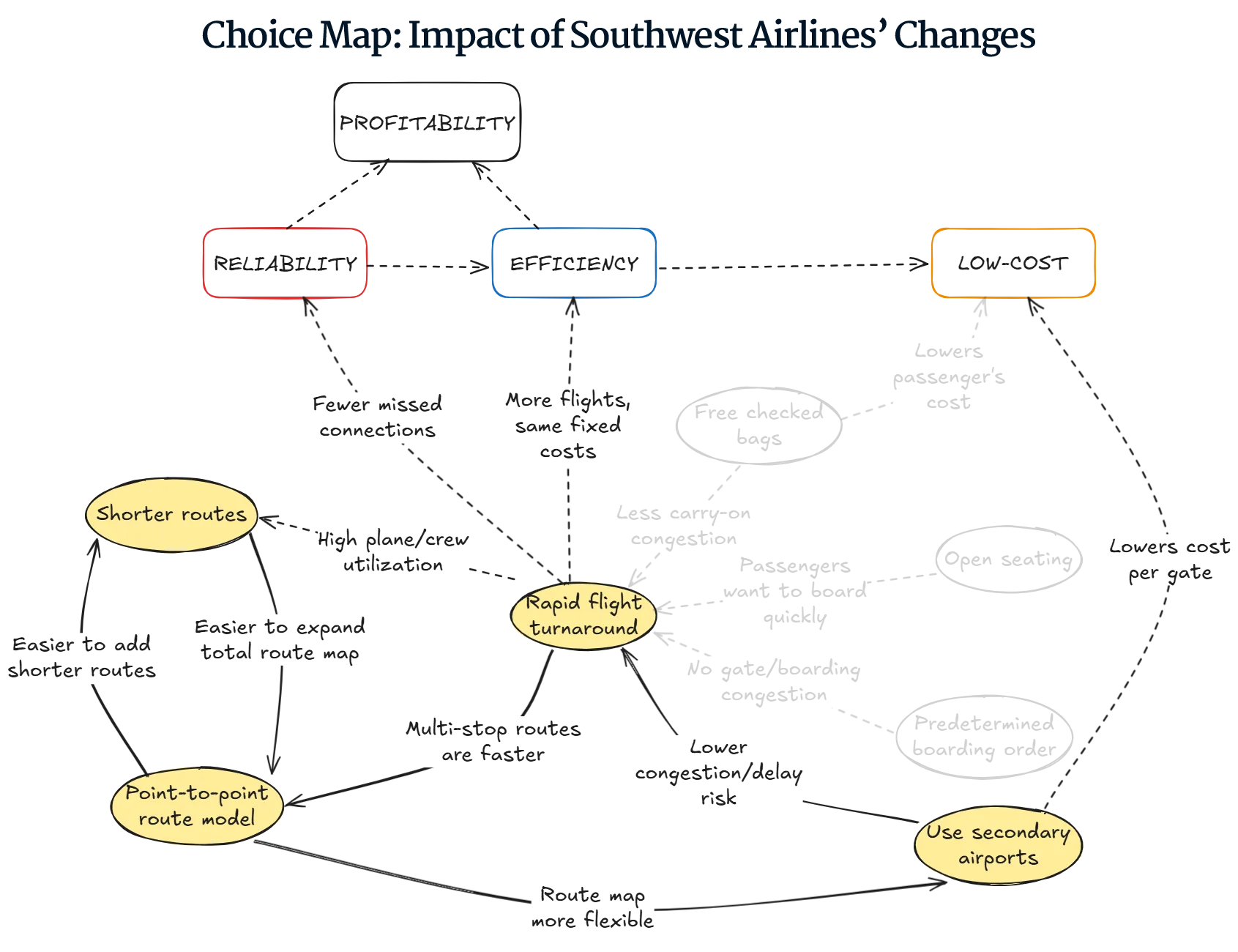

Southwest recently announced a number of big changes to its operations. These were made in response to demands from activist investor Elliott Investment Management. Elliott addressed the Southwest board on behalf of its funds in a letter that, among other things, expressed concerns about Southwest’s profitability and recent stock price performance. Among the changes are the elimination of: open seating, the predefined boarding order, the single class cabin, and free checked bags. In Southwest’s choice map, all of those choices have reinforcing relationships that both create competitive advantage and support Southwest’s goals.

Southwest will soon adopt reserved seating and more expensive “premium” seat classes, just like on conventional airlines. I thought they could preserve Southwest’s unique concept of a reserved place in line for each passenger, even with reserved seating. But, several months after announcing the switch to conventional reserved seating, their EVP of operations explained that planes will board by “smaller groups” and will have “more ordinal boarding”. That sounds like the conventional airline boarding process.

Now, certainly there are some people who didn’t fly Southwest because they don’t like open seating. Southwest’s theory here may be that they can pick up some passengers from conventional airlines because they’ll look more like a conventional airline. Also, The end of free checked bags will almost certainly lead to higher revenue per customer. People who used to check bags for free will now have to pay to do that. If everything else stayed the same, it’s fair to say that these changes would increase Southwest’s revenue per passenger. And some passengers who didn’t used to fly Southwest might decide to try it. But, when you look at strategic changes in isolation, it’s easy to miss the potential impact on the broader strategy.

Impact on Operations

It’s very clear in Southwest’s choice map that the success of their other choices and impact on their goals depend on their current ability to turn flights around faster than a conventional airline. That enables them to get strong positive impact from choices like point-to-point routes and shorter routes. The Mythbusters offered compelling evidence that Southwest’s boarding process will slow down when they start assigning seats. The addition of a financial incentive to carry on more bags will further increase delays that result from the combination of assigned seats and limited overhead bin space.

With these changes, Southwest’s other choices that create their unique strategy, such as point-to-point flight routes, will have less positive impact on their goals. The slower flight turnaround will make it more difficult for Southwest to fly popular, shorter routes more efficiently than its conventional airline competitors. With the announced changes, Southwest will likely need to adjust its flight schedules to allow more time to turn flights around. That means it won’t be able to fly as many trips per day on a given route. To counter delays, Southwest could just put more planes in the air along the routes, but that will increase their costs. Either way, they’ll be less efficient and less competitive on those shorter routes on which they’ve built their route map.

Also, the new boarding process and paid checked bags will create more uncertainty in departure times. This increases the likelihood of delays. Southwest’s shorter routes could compete with conventional airlines’ longer non-stop routes because the airline could efficiently and reliably connect several point-to-point routes together to fly passengers longer distances at lower prices. The changes will increase the risk of missed connections and longer layovers. This will make Southwest’s route model less competitive and their flight plans less attractive for longer routes. Southwest’s operations will begin to look more like those of a conventional airline, even though their route map will be quite different. Conventional airline operations aren’t designed to accommodate the point-to-point model. It’s not clear that mixing conventional operational choices with a totally different route model will work.

Impact on Goals and Customers

The company’s strategy will soon be at odds with some of its goals. This is not a recipe for success. Remember, the company’s “Purpose” is to provide “low-cost air travel”. Increasing revenue per passenger is not something you do in pursuit of providing the lowest-cost travel option. Even if Southwest aims to keep the average cost for a route lower than that of its competitors, its strategy still won’t support its goals. Southwest’s “Vision” is to be the “most efficient, and most profitable airline”. We know it’s likely that that the announced changes will lower Southwest’s efficiency. It will be more difficult for it to fully utilize its expensive resources and people. Lower efficiency makes it difficult to keep prices low without putting pressure on profitability.

Putting aside Southwest’s goal of providing “low-cost air travel”, it’s possible the shareholders pushing for these changes believe that higher revenue per passenger will make up for some loss of efficiency. In fact, most of the new changes are clearly designed to increase Southwest’s revenue per passenger. Charging fees to check bags or to access premium seats would increase the average amount of money Southwest receives from a passenger for each flight. In other words, the shareholders are probably correct that revenue per passenger will icnrease. The problem is that the changes may reduce the number of passengers.

This is because Southwest’s strategy has historically made it very different from its competitors. Customers that choose to fly Southwest are choosing a very different experience from most other airlines. People who regularly fly on Southwest its ideal customers. They fly with Southwest because of the ways it’s different form other airlines. Southwest’s changes will make it look a lot more like all the other airlines. Southwest’s ideal customers will be more willing to fly on a conventional carrier instead, if Southwest no longer offers the unique features that made the customers loyal in the first place. But what kind of impact do loyal customers really have on Southwest’s revenue? As an outsider to a company, it’s difficult to directly measure customer loyalty. But, there are indications in Southwest’s financial results.

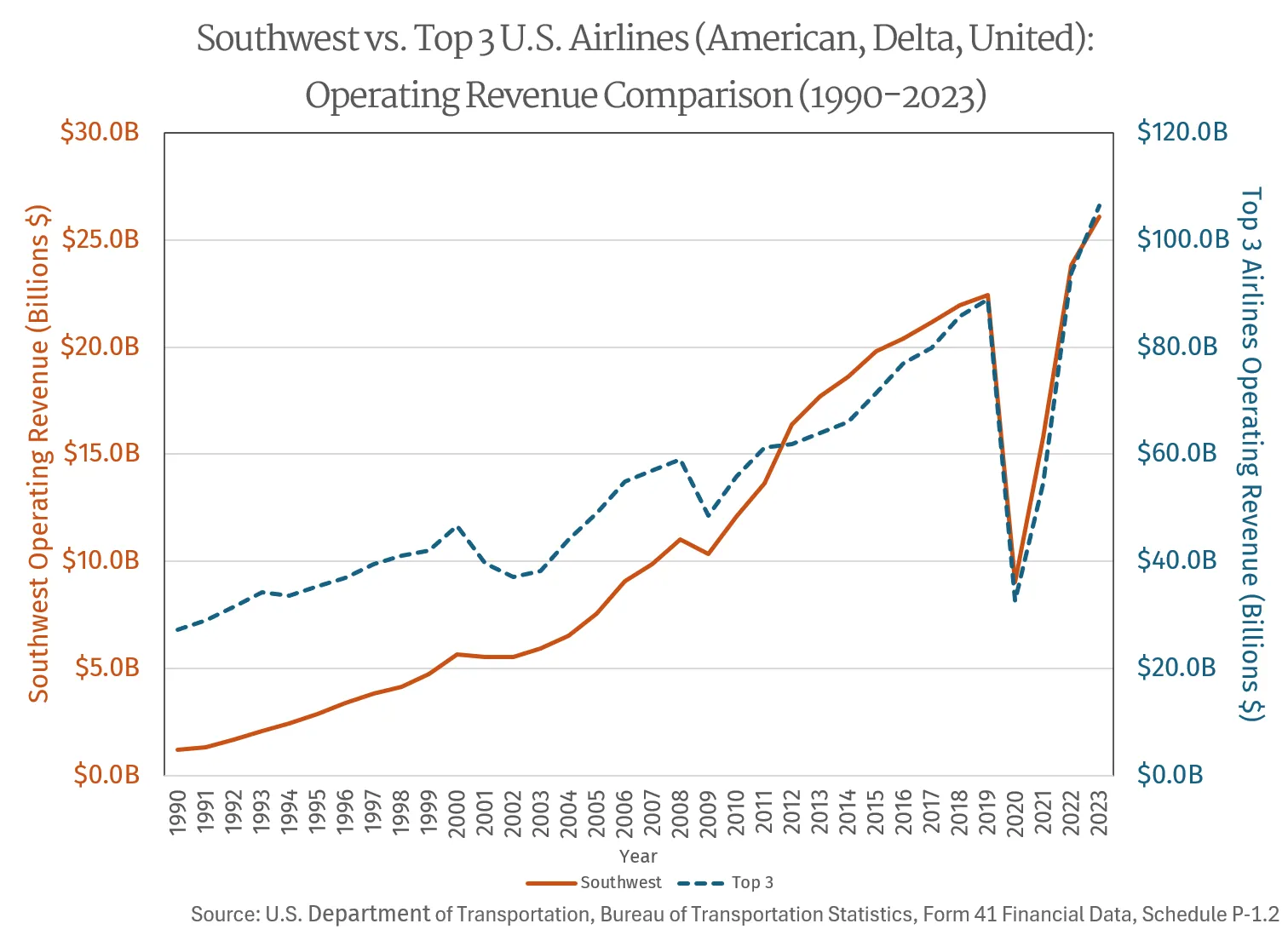

What makes a customer “loyal” is that they buy a product predictably. To visualize customer loyalty, it’s useful to look at Southwest’s operating revenue over time vs. the other “top three” U.S. airlines (American, Delta, and United). What you see is more stable, higher growth and less volatility in Southwest’s revenue than in the “rest” of the industry. This implies that Southwest is finding and retaining the right customers. Of course, air travel is impacted by major recessions in the early 2000’s and around 2008, but the impact on Southwest’s revenue is noticably less severe. It’s a bit outlier, but I included the post-2019 performance on the chart because it’s important to appreciate the universal impact the declaration of a global pandemic had on air travel. By finding and keeping loyal customers that value Southwest’s model and all of the company’s choices, it is more insulated from the cylical swings and commoditization of air travel. If their service begins to look like that of the other big three airlines, Southwest will need to compete more directly for its previously loyal customers. I would expect its revenue to be more volatile and its growth less predictable as a result.

Southwest’s “Purpose” and “Vision” were designed to attract and retain a certain type of customer. Its current passengers fly Southwest because they value all the things that Southwest talks about in its “Purpose” and “Vision”. Those customers accept the tradeoffs of things like using secondary airports, having connections in less popular cities, and not having reserved seats because they value lower cost and higher efficiency. Otherwise they’d just fly a conventional airline. Once Southwest’s strategy no longer supports doing the things its customers value most, it’s easier for those customers to shop somewhere else. If there’s a large enough drop in passengers, it will erase the gains made by increasing the amount of revenue they get from each passenger. At the same time, the company’s profit margin may decrease. Unfortunately, the most important strategy lesson we learn from Southwest may be the negative financial impacts of voluntarily giving up competitive advantage.

Maintaining Competitive Advantage

If you understand your company’s strategy, you can avoid eliminating important choices and eroding the company’s competitive advantage, as Southwest has done. Through analysis like a choice map, you’ll know which choices directly support the company’s goals or provide indirect support by reinforcing other choices. Internally, you’ll know how to avoid making changes that weaken the company’s strategy. Externally, however, you should expect competitors to threaten your company’s competitive advantage. They will often do this by copying choices that have worked well for your company.

You can prepare for this by proactively thinking about competitive threats to your company’s strategy. Look at each choice on your choice map and ask yourself how difficult it would be for competitors to copy it. Don’t just think about easy it is for competitors to implement the choice, but also whether that choice aligns or conflicts with their other choices. If the choice isn’t compatible with your competitors’ strategies, it probably won’t help them as much as it helps you. On the other hand, if the choice would be supported or reinforced by your competitors’ other choices, they could eliminate some of your company’s competitive advantage by copying that choice.

If you think a competitor could benefit from copying one of your company’s choices, you have a couple of options. You can slightly modify what your company is doing to make it less compatible with your competitor’s strategy. You could also try to preserve the positive impact of the choice by adding unique supporting or reinforcing choices to your strategy. The goal is for the choice to provide greater impact for your company than it can provide for your competitors. If you think the choice is likely to become widely adopted in the industry, then it will be difficult to preserve the competitive advantage it provides for your company. If so, you’ll need to accept that you were simply an early adopter of a new industry standard. In the airline industry, Alaska Airlines was the first to offer online check-in to passengers. Since it wasn’t uniquely beneficial to Alaska Airlines’ strategy, the rest of the industry soon adopted it. If it’s too challenging or costly for your company to preserve the advantage a choice creates, you’ll need to accept that the choice is no longer strategic and disregard it when thinking about your company’s strategy.

Even if many of your company’s choices are unique and unlikely to be imitated, it’s still a good idea to protect your company’s advantage. You should think about new ways to support and reinforce those choices. To do that, think about adding things like corporate activities, features of your products and services, and sales channels that would support your company’s existing unique strategic choices and goals. Think about the current impact of your company’s most important choices and consider how that impact could be increased. To maintain competitive advantage, a company needs to be proactive and intentional about its strategy.

Managing Strategic Change

A company’s strategy is not static. As the industry changes around it, a company must adapt. Amazon, for example, has modified its strategy over the years. It used to be purely an e-commerce company. As it grew, the company developed a lot of its own technology to run the primary business, Amazon.com. That business needed a lot of computers and storage available to handle seasonal spikes in shopping associated with holidays and promotions. Most of the time, Amazon didn’t need those resources. With an increase in businesses building and hosting enterprise software online, Amazon increased the value of owning extra computing resources by choosing to become a cloud computing provider. It now sells usage of idle infrastructure to other companies through its Amazon Web Services unit, which is approaching 20% of Amazon’s total revenue.

But constantly making changes to strategy can be counterproductive. Starting and stopping initiatives wastes valuable time and money. Also, if a company is constantly changing direction, it’s difficult for employees to figure out what they’re supposed to be working on. This leads to a lot of waiting and not much progress towards goals. But, as your company develops, you will find new opportunities and come up with ideas for new things like products, services, and distribution mechanisms. These will have costs and tradeoffs, so it’s important to evaluate each new idea carefully.

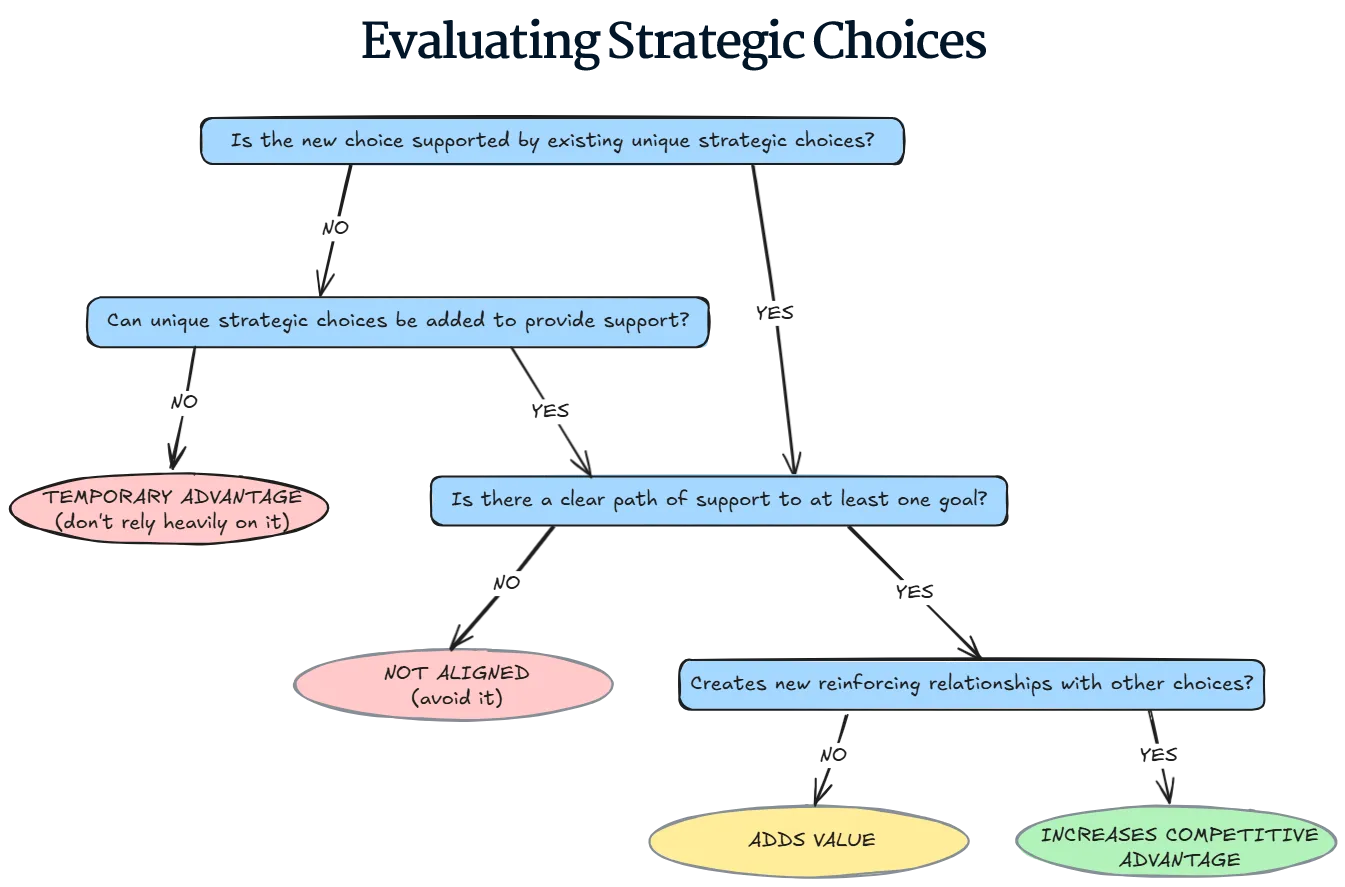

This starts with understanding if the idea will impact the company’s strategy at all. That is, understanding if the idea is a strategic choice. You can follow the earlier chart to figure that out. If the idea is just a tactical decision, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do it. But if it will be expensive and it doesn’t seem risky to not do it, then you might want to skip it. If the idea is a strategic choice, then you should think about how it could strengthen your company’s strategy.

First, since the whole idea of a strategic choice is that it provides competitive advantage, evaluate how durable the advantage will be. If your company hasn’t made other unique choices that support and reinforce the new choice, competitors can easily copy the idea and get the same benefits. Also, if you think the idea will eventually be widely adopted as an industry standard, it will only provide temporary competitive advantage.

Next, make sure the choice directly or indirectly supports your company’s goals. On your choice map, there should be a path of support from the new choice to at least one goal. If the new choice creates a reinforcing relationship with other choices, that increases its strategic value. You might be less sensitive to the cost of adopting the choice if it creates new reinforcing relationships in the strategy. If there aren’t strong supporting relationships between the opportunity and the existing choices, you should think about additional strategic choices that would provide more support for it.

You should follow this process with every significant activity that is proposed within your company. If you’ve identified an actual strategic choice that will support your goals and has good support or reinforcing relationships within your existing set of choices, that’s a strong signal that it’s worth pursuing. It’s a good practice to revisit your strategy periodically to make sure that your choice map is up to date with activities your company has discontinued or modified. Also, think about any sets of choices that have become so common in the industry that they’ve lost their unique strategic value and should no longer be considered part of your strategy.

Conclusion

For Southwest Airlines and, in fact, for any business, the company’s mission is its reason for existing. Ultimately that reason ties directly to customers. Without customers, there is no business. A company’s mission articulates the value it provides to customers. It also guides the choices the company makes. Those choices must support the mission and its implied goals, making it easier for the company to achieve them.

Inevitably, choices will have trade-offs. The other choices a company makes should mitigate the negative impacts of those trade-offs. To create more durable competitive advantage and avoid becoming like a commodity, a company should make strategic choices that provide it with greater benefits than the choices would provide to its competitors. The idea is to make it unattractive for competitors to copy what the company is doing. This ensures that a company’s combination of choices creates a truly unique strategy in its industry.

Southwest’s history has demonstrated the power of a well-designed strategy. For decades, the airline created exceptional value for customers through a system of mutually reinforcing choices that aligned with its mission of providing low-cost, reliable air travel. The boarding process supported the route structure, which supported the airport choices, which supported the fast turnaround times. The company’s unique choices created a unique strategy and success that competitors couldn’t copy.

With the changes Southwest has proposed, the company’s strategy is now more of a cautionary tale. Even a successful company can forget about its broader strategy and pursue initiatives that look promising in isolation, but actually reduce the support and reinforcement of other choices in its strategy. Unfortunately, what I think we’re going to see with Southwest Airlines is the eventual weakening of its strategic advantage.

Some unique choices remain in Southwest Airlines’ strategy, but, since it has abandoned several important ones, it isn’t as good an example for me to use when explaining what great strategy looks like. If there’s any consolation, it is that we can look at Southwest’s past to see what winning strategy looks like, even if its present and future success are questionable.

As you build and expand your own company’s strategy, think about conducting an analysis and ongoing review of its strategic choices. Identify which choices directly support the mission and goals, which choices reinforce each other, and which choices might not be worth the cost. Avoid making Southwest’s mistake of abandoning choices that provide important competitive advantage. Ultimately, great strategy isn’t about making individual choices. It’s about creating a system of interconnected choices where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Image Credits

Figure 1: United and Continental Airlines Route Map 2010 (United_Continental_Route_Map_2010.jpg) Credit: airbus777 at flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0

Figure 2: Southwest Airlines Route Map 2011 (Southwest_Airlines_Route_20110327.png) Credit: Cassiopeia sweet at Japanese Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

All Other Images generated using ChatGPT, then modified and edited by Jason Roth